In our mini-series about the myths of Psychology, the next one is that Psychologists know what you are thinking or are analysing you in every conversation they have.

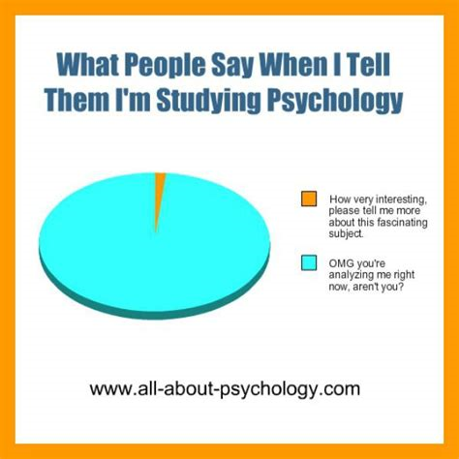

This pie chart sums it up nicely.

Actually, this myth gives us plenty of interesting things to talk about – each of which could be a blog in their own right. I’ll try and keep it brief (anyone who knows me will know that this isn’t always something I manage!)

One really interesting model for thinking about this is called ‘mentalisation’. Mentalising is the skill of thinking about your own and others’ minds. Firstly, a key part of developing your intrapersonal skills is recognising that we can never know what another is thinking with complete certainty. We can often make inferences based on the external, observable things like their facial expressions or the way they behave. We also have a better chance of getting it right if we know the person, simply because we’re better at picking up on these external cues and because we may have talked with them about their thinking in the past. But still, even with our nearest and dearest we can’t always know what they are thinking. A Psychologist doesn’t have any magical powers to see inside your head. They use the same cues you do to interpret what is happening. They might also use their knowledge of theories or human behaviour or their clinical experience which might help them to get it right more of the time, but it’s no guarantee. So be reassured, your thoughts are safe!

Very small children don’t have what we call a ‘theory of mind’ – this is the idea that different things go on inside different minds. There’s a couple of classic tests that demonstrate this well. In one such test a pencil is placed inside a tube of Smarties. When you ask a small child (or anyone) what they think is inside the tube, they are most likely to say ‘Smarties’ (for the non-UK reader these are small coloured chocolate sweets). They have used the information available to them and drawn a sensible conclusion. But then they are shown the pencil. They are asked what they think the next child will say to the question about the tube. Small children respond ‘a pencil’. Because they know there is a pencil in there, they assume that everyone knows this. It’s only after a certain age that they start to realise that what’s in their head is not the same as in others.

But, even with this development, small children are not as able to mentalise as adults – they have not yet developed the mental apparatus or the experience to do this. That’s why small children are surprised when an adult correctly guesses their motives for something or predicts their mischief before they’ve even done it. As an adult it may be obvious (written all over their cheeky grin) but to the child this really is magical – that someone could see inside their head and see their thoughts.

As we progress through childhood these skills develop and they continue to develop in adulthood too. We can get better at mentalising. Psychologists will (hopefully) have developed these skills through their extensive training and clinical practice. But this doesn’t mean we would analyse everyone we see. When we’re chatting at a party or over Sunday lunch, we’re just chatting because we’re interested. When we are talking to children or parents at Headspace Guildford, we are talking because we want to hear what they have to say, not because we want to come up with clever interpretations of our own. I always tell children, ‘you are the expert in you’. The more honest you are, the more you’ll get out of coming and be reassured that there’s no magic going on – no seeing inside your head or analysing your every breath. Clinical Psychology is about people and what they bring and what they’re going through or managing. It’s a very human, grounded interaction. It’s not magic that it works – there’s good evidence about what it works (a future blog I think!) and it’s nothing sneaky. Trust in the good that two people working together as equals can achieve.